Insights from these analyses stem from a cross-sectional dataset of around 2,000 households spanning four regions of Mali (Kayes, Koulikoro, Ségou and Sikasso). The dataset was collected by IITA during the 2019 production season and provides a comprehensive resource from which was extracted and model the relationships of key characteristics associated with adoption. These range from frequently utilised socioeconomic and farm characteristics to aspects concerning social integration and provisioning of financial and advisory services.

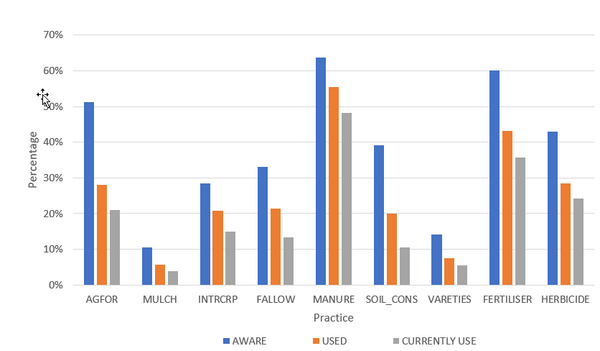

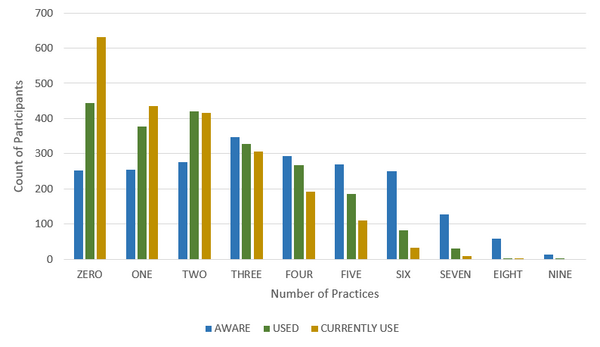

The current use of the six most widespread agroecological practices (Agroforestry (AGFOR), Mulching (MULCH), Intercropping (INTRCRP), Improved Fallows (FALLOW), Manure Composting (MANURE), Cordon Pierreux (SOIL_CONS)) alongside the three most common conventional practices was modelled (Improved Varieties (VARIETIES), Synthetic Fertiliser (FERTILISER) and Herbicide usage (HERBICIDE). See fig.1 for an overview of awareness, past and current usage. The final three practices were included to see if there was a substitution between agroecological and more conventional practices.The analysis was performed with a multivariate probit model, which considers joint decision-making on the implementation of the selected practices. This allows representation of substitution or complementation effects between the numerous uptake decisions presented. Various specifications of the model yielded consistent evidence that there appears to be a great deal of complementarity between practices. For example, it was found that a farmer adopting agroforestry was significantly more likely to also adopt improved fallows, intercropping, decomposed manure and improved varieties (see fig. 2 for an indication of the frequency of various levels of multi-practice awareness and usage).

Whilst controlling for a large number of farm characteristics, the results consistently presented highly significant, positive, trans-practice associations between the adoption decision and key leverage variables related to services and networks. For instance, access to extension and credit, training about practices, higher integration of family members in groups, membership in a well-functioning agricultural cooperative and gaining information from either relatives or other farmers, were all positively associated with the adoption of agroecological practices. Furthermore, the level of practice adoption within the respective community, as well as land ownership, showed strong associations with adoption. Whilst this approach remains rather exploratory in nature, these initial findings present interesting considerations for policy makers and indicate focus areas meriting further analysis.

Next steps

In the next steps of the analyses, Work Package 3 will expand the robustness of these exploratory findings by conducting a similar multivariate analysis on recently available farm-level data from Senegal. Once this is complete, they aim to break down and explain any discernible causal interactions of key variables in the adoption process. This second stage will look deeper at the effects of credit, extension and training on adoption. Moreover, the advanced econometric models will also try to factor in the likelihood that differences in the level of awareness of agroecological practices could lead to exposure bias in the estimations. Subsequently, the analysis will expand this framework to the level of adoptive behaviour across all six agroecological practices by utilising a similarly specified ordered probit model, whereby adoption will be ranked on a 7-point scale. The scale will range from 0 to 6, where 0 equates to no practice adopted and 6 signifies that all practices are adopted.

Finally, there are two additional aspects that have not yet been considered in great detail; these are accounting for (1) the extent of practice adoption (proportion of farm area enrolled) and (2) the factors affecting dis-adoption. Amalgamation of these aspects into the study will help to provide a holistic insight into the decision-making process and preferences of growers in the Sahel region. The WP3 teams looks forward to diving deeper into analysis and sharing the final results with you all over the coming months.

Written by: Christian Grovermann, WP3 leader and Charles Rees from FiBL

tap and then scroll down to the Add to Home Screen command.

tap and then scroll down to the Add to Home Screen command.